Rural Manitoba and the Pandemic

Dr. Danielle Paradis reflects on responding to COVID in a small rural community.

By Ashley Smith

During the first two weeks of the pandemic, everything changed so quickly. In Manitoba, the lockdown came swiftly, and even in the small town of Ste. Rose du Lac, located about 270 km northwest of Winnipeg, it was clear, the virus was coming.

Dr. Danielle Paradis is a rural practitioner with the Prairie Mountain Regional Health Authority (RHA). Based in Ste. Rose du Lac, she splits her time between East Parkland Medical Group, a private practice, and the Ste. Rose du Lac General Hospital. She is one of five emergency doctors on-call there and focuses heavily on geriatric medicine.

Born and raised in the small community of Dunrea, southeast of Brandon, Dr. Paradis saw first-hand the results of the ongoing shortage of rural physicians. Studying medicine, she always knew she wanted to be in a rural practice.

“When my patients realize I studied here and stayed here, it builds trust and gives them a sense of longevity,” Dr. Paradis explains. With just under 1,000 people, Ste. Rose is a vibrant collection of farming communities with a relatively sizeable francophone population, and the catchment of local First Nation reserves.

Her patients vary from those in extreme poverty to those who are relatively affluent for a rural area. “But some may travel two hours to the hospital, so you can see the impact of not being able to just pop into the doctor’s office to talk about their health conditions, such as diabetes.”

The remote location means something else, as Dr. Paradis notes. “You learn to work with less, the resources are just not there.” Last year, Dr. Paradis wrote an open letter raising concerns regarding looming changes to rural health care and how it could leave hospitals scrounging for resources.

With resources at a minimum, Dr. Paradis and her team braced for impact as COVID-19 entered Ste. Rose du Lac.

“We immediately created a COVID-19 ward by converting office space into rooms,” she explains. “We created a COVID-specific medical unit in anticipation of what was coming. And we layered up in whatever available PPE we could get our hands on.”

“It’s always been the case that when it comes to supplies, larger communities get first dibs and rural communities take what’s left,” she notes.

While trying to prevent panic in her community, it was clear that the fear of COVID-19 was present. The team referred to suspected cases as Code 19s. “There was one day with eight patients that came in with a Code 19 – that’s a significant amount.” Struggling for proper equipment, they were thankful for PPE and handcrafted items, such as cloth facemasks, donated by locals.

While province-wide the infection rate dropped over the summer, a surge in western Manitoba made people look at hospitals within Prairie Mountain Health with disdain. “It was a kind of COVID-shaming. People asked, ‘What are you guys doing wrong?

Can’t you get it under control?’ That made it tough for communities like Ste. Rose.”

However, by October, the second wave would sweep across the entire province, with Winnipeg experiencing the same tougher restrictions to try to slow the spread of COVID-19.

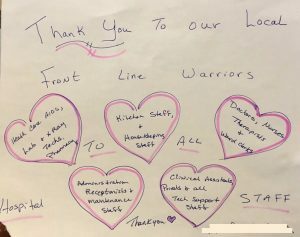

In some ways, Dr. Paradis says the people of Ste. Rose are lucky because it’s a smaller community. “We know the team, the cleaning staff, the front staff, and we know who is screening the patients. ‘Thank you’ cards and messages of support come from the community: they keep up morale. We know we are in this together.”

As she tells her patients, there’s still a long winter ahead before enough people can get immunized. Nevertheless, Dr. Paradis and her small-town team’s commitment and innovative spirit are what makes rural doctors and the Manitobans they serve proud of the work they do.